The Luddites have a bad reputation.

These days, the word is most commonly used as an insult—shorthand for somebody who doesn’t understand new technology, is skeptical of progress, and wants to remain stuck in the ways of the past.

That perception couldn’t be more wrong, according to Brian Merchant. In his new book, Blood in the Machine, Merchant argues that understanding the true history of the Luddites is vital for workers today grappling with the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and automation in the workplace.

“At least in my lifetime, the Luddites have never been more relevant,” Merchant, 39, tells TIME. “We are confronting a series of cases where technology is being used by tech companies and executives in different industries as a means of trying to drive down wages and worsen conditions so that the entrepreneurial class can make more money.”

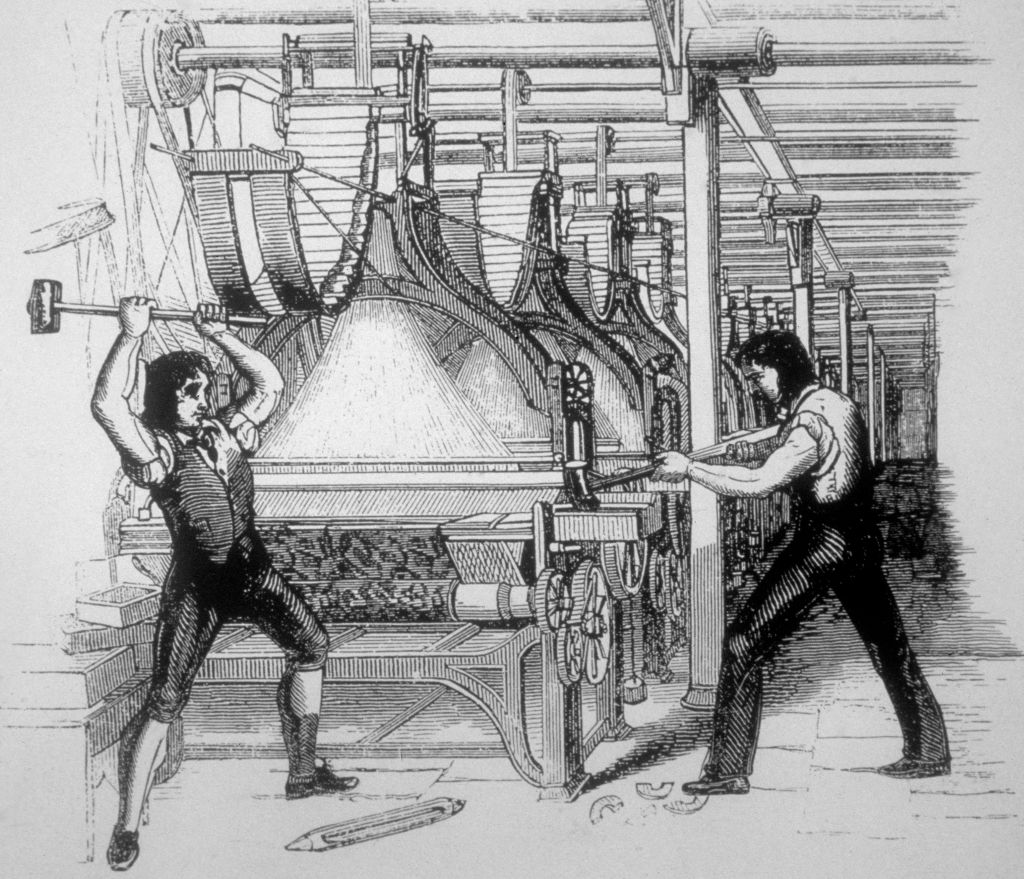

If you know anything about the Luddites, you probably know that they were English textile workers who, at the dawn of the industrial revolution, resisted the introduction of new machinery. They would sneak into factories in the dead of night and destroy the power-looms they believed were threatening their jobs.

That much is true. But, as Merchant’s book outlines in detail, it is an incomplete picture. The Luddites were not anti-machinery; many of them were machine experts and welcomed the introduction of new equipment that made their work easier. What they opposed was a choice—presented as an inevitability—made by a class of factory owners in the early 19th century. Instead of seeing machines as a way to support their expert workers, they introduced industrial machinery that could make large quantities of textiles faster and more cheaply than clothworkers working by hand. These simple new machines meant factory owners began employing more lower-skilled and therefore lower-waged workers—often child laborers—instead of skilled clothworkers with years of training. The cloth these machines produced was lower quality, but it was so cheap to churn out, and there was so much of it, that the factory owners still turned a profit.

The Luddites correctly recognized that this shift was not only debasing their art and depressing their wages, but also changing the very nature of what it meant to work. In the place of a “cottage industry” where clothworkers, often working from home, could work as many or as few hours in the day as suited them, a new institution was arising: the factory. Inside the factory, workers would work long hours at dangerous machinery, be fed meager meals, and submit to the punitive authority of the foreman. The Luddites saw that the winners from this technological “progress” would not be workers—neither the expert textile makers losing their jobs, nor the exploited children replacing them. The winners were the factory owners who, having found a new way to disempower their workers, were able to amass a greater share of the profits those workers generated.

Labor organizing at the time was illegal, so workers had few legal means of protest. The Luddites decided, instead of going after factory owners, to destroy the machines. But not any machines. They would target only the factories whose owners they believed were using new machinery as a pretense to erode their livelihoods. They would warn them in advance, giving them a chance to change their practices; some owners took it. Eventually, however, industrialists and the state came together, and British troops were sent to violently crush the Luddite movement.

Merchant is far from the first to argue the Luddites are deserving of a historical reappraisal. The social historian E.P. Thompson documented their movement in the 1960s and argued it was the first time industrial workers began to conceive of themselves being members of a single political group: the working class. But where Blood in the Machine is unique is in the parallels it draws with the 21st century economy.

Those parallels, Merchant says, are visible across industries: from the art world—where AI-generated imagery is depressing illustrators’ wages—to transit, where ride-hailing services like Uber and Lyft have turned taxi-driving into an unprofitable and insecure profession. And in the entertainment industry, Merchant notes, writers and actors have been striking to protest attempts by studios to use AI to degrade their pay and job stability.

“If you look at the writers and the actors who are on strike today, they’re not worried that AI is going to write the next Martin Scorsese movie,” Merchant told TIME on Sept. 13. “They’re worried that it’s going to churn out something deemed good enough by the studios, who will then send it to the writers for a rewrite fee, and not give them full ownership of the script, and the writers will make less money. That technology is being used deliberately as leverage against the workers. And that pattern is eerily similar to what was happening in the Luddite day: the way that technology doesn’t really replace workers, because it can’t, but it is used to degrade their livelihoods, to cut down their wages, and to break their power.”

Read more: 4 Charts That Show Why AI Progress Is Unlikely to Slow Down

The Luddites, of course, failed. Automated machinery of the kind they were resisting kicked off the industrial revolution—and while many millions of people were immiserated in factories as a result, there is no denying that this process made goods cheaper and more accessible, driving up the average standard of living. But in the process, Merchant argues, the ruling classes popularized the pejorative definition of Luddism that exists to this day, not only to discourage workers from coming together and threatening their property, but also to dilute their wider political message. That message? That if new technologies erode wages and increase wealth inequality, it’s a result of a political choice by the owners of that technology, not a result of the inevitable and unstoppable march of progress. And that therefore, a more equitable way forward is possible—keeping the benefits of technology, but sharing its proceeds more widely. As Merchant puts it: “we can absolutely decide how we want technology to be used.”

It’s that political message, not the machine-smashing, that Blood in the Machine attempts to rehabilitate. (Not that destroying AI or other forms of automation would even be possible in most cases, Merchant notes, given that taking a hammer to globally-distributed software corporations is pretty difficult.) The book casts Luddites not as backward technophobes, but as a prescient movement from whom a new generation of worker activists can learn plenty. “We should be Luddites,” Merchant says. “The Luddites were making a powerful complaint. If we reclaim what they were actually trying to say, we can apply the lessons of their story to today, and prevent a lot of misery.”

Write to Billy Perrigo at billy.perrigo@time.com